Crazy Horse (band) Songs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Crazy Horse ( lkt, Tȟašúŋke Witkó, italic=no, , ; 1840 – September 5, 1877) was a

Sources differ on the precise year of Crazy Horse's birth, but most agree he was born between 1840 and 1845. According to Šúŋka Bloká (

Sources differ on the precise year of Crazy Horse's birth, but most agree he was born between 1840 and 1845. According to Šúŋka Bloká (

McGillycuddy, who treated Crazy Horse after he was stabbed, wrote that Crazy Horse "died about midnight." According to military records, he died before midnight, making it September 5, 1877.

McGillycuddy, who treated Crazy Horse after he was stabbed, wrote that Crazy Horse "died about midnight." According to military records, he died before midnight, making it September 5, 1877.

Most sources question whether Crazy Horse was ever photographed.

Most sources question whether Crazy Horse was ever photographed.

The Final Days and Death of Crazy Horse

Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part 1 DVD

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Crazy Horse 1840s births 1877 deaths 1877 murders in the United States Lakota leaders Murdered Native American people Native American history of South Dakota Native American people of the Indian Wars People of the Great Sioux War of 1876 Red Cloud's War People of the American Old West Deaths by stabbing in the United States People murdered in Nebraska Battle of the Little Bighorn

Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

*Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

*Lakota, Iowa

*Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

*Lakota ...

war leader of the Oglala

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota, make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority of the Oglala live o ...

band in the 19th century. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by white American settlers on Native American territory and to preserve the traditional way of life of the Lakota people. His participation in several famous battles of the Black Hills War

The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations that occurred in 1876 and 1877 in an alliance of Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne against the United States. The cause of the war was the ...

on the northern Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

, among them the Fetterman Fight

The Fetterman Fight, also known as the Fetterman Massacre or the Battle of the Hundred-in-the-Hands or the Battle of a Hundred Slain, was a battle during Red Cloud's War on December 21, 1866, between a confederation of the Lakota, Cheyenne, and ...

in 1866, in which he acted as a decoy, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

in 1876, in which he led a war party to victory, earned him great respect from both his enemies and his own people.

In September 1877, four months after surrendering to U.S. troops under General George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan ...

, Crazy Horse was fatally wounded by a bayonet-wielding military guard while allegedly resisting imprisonment at Camp Robinson in present-day Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

. He was honored by the U.S. Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an independent agency of the executive branch of the United States federal government responsible for providing postal service in the U. ...

in 1982 with a 13¢ Great Americans series

The Great Americans series is a set of definitive stamps issued by the United States Postal Service, starting on December 27, 1980, with the 19¢ stamp depicting Sequoyah, and continuing through 1999, the final stamp being the 55¢ Justin S. Mo ...

postage stamp.

Early life

Sources differ on the precise year of Crazy Horse's birth, but most agree he was born between 1840 and 1845. According to Šúŋka Bloká (

Sources differ on the precise year of Crazy Horse's birth, but most agree he was born between 1840 and 1845. According to Šúŋka Bloká (He Dog

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

), he and Crazy Horse "were both born in the same year at the same season of the year," which census records and other interviews place in 1842. Ptehé Wóptuȟ’a (Encouraging Bear

Encouraging Bear, also known as Horn Chips (Lakota: ''Ptehé Wóptuȟ’a'' (in Standard Lakota Orthography)), was a noted Oglala Lakota medicine man, and the spiritual advisor to Crazy Horse.

Horn Chips was born in 1824 near Ft. Teton. He was ...

), an Oglala medicine man

A medicine man or medicine woman is a traditional healer and spiritual leader who serves a community of Indigenous people of the Americas. Individual cultures have their own names, in their respective languages, for spiritual healers and ceremo ...

and spiritual adviser to Crazy Horse, reported that Crazy Horse was born "in the year in which the band to which he belonged, the Oglala, stole One Hundred Horses, and in the fall of the year," a reference to the annual Lakota calendar or winter count

Winter counts (Lakota: ''waníyetu wówapi'' or ''waníyetu iyáwapi'') are pictorial calendars or histories in which tribal records and events were recorded by Native Americans in North America. The Blackfeet, Mandan, Kiowa, Lakota, and other Pla ...

. Among the Oglala winter counts, the stealing of 100 horses is noted by Cloud Shield, and possibly by American Horse

American Horse ( lkt, Wašíčuŋ Tȟašúŋke) (a/k/a "American Horse the Younger") (1840 – December 16, 1908) was an Oglala Lakota chief, statesman, educator and historian. American Horse is notable in American history as a U.S. Army Indian S ...

and Red Horse owner, as equivalent to the year 1840–41. Oral history accounts from relatives on the Cheyenne River Reservation

The Cheyenne River Indian Reservation was created by the United States in 1889 by breaking up the Great Sioux Reservation, following the attrition of the Lakota in a series of wars in the 1870s. The reservation covers almost all of Dewey ...

place his birth in the spring of 1840.''The Authorized Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part One: Creation, Spirituality, and the Family Tree'', DVD William Matson and Mark Frethem, Producers.(Reelcontact.com Productions, 2006). On the evening of his son's death, the elder Crazy Horse told Lieutenant H.R. Lemly that the year of birth was 1840.

Immediate family

Crazy Horse was born to parents from two different bands of theLakota

Lakota may refer to:

*Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

*Lakota, Iowa

*Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

*Lakota ...

division of the Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

, his father being an Oglala

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota, make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority of the Oglala live o ...

and his mother a Miniconjou

The Miniconjou (Lakota: Mnikowoju, Hokwoju – ‘Plants by the Water’) are a Native American people constituting a subdivision of the Lakota people, who formerly inhabited an area in western present-day South Dakota from the Black Hills i ...

. His father, born in 1810, was also named Tȟašúŋke Witkó (Crazy Horse). Crazy Horse was named Čháŋ Óhaŋ (Among the Trees) at birth, meaning he was one with nature. His mother, Tȟašína Ȟlaȟlá Wiŋ ( Rattling Blanket Woman, born 1814), gave him the nickname Pȟehíŋ Yuȟáȟa (Curly Son/Curly) or Žiží (Light Hair) as his light, curly hair resembled her own. She died when Crazy Horse was only four years old.

One account said that after the son had reached maturity and shown his strength, his father gave him his name and took a new one, Waglúla (Worm). Another version of how the younger Crazy Horse acquired his name is that he took it after going through the haŋbléčheya ceremony. Crazy Horse's cousin (son of Hewáŋžiča, Lone Horn

Lone Horn (Lakota: Hewáŋžiča, or in historical spelling "Heh-won-ge-chat" or "Ha-wón-je-tah"), also called One Horn (1790 –1877), born in present-day South Dakota, was chief of the Wakpokinyan (Flies Along the Stream) band of the Minnec ...

) was Maȟpíya Ičáȟtagya (Touch the Clouds

Touch the Clouds (Lakota: Maȟpíya Ičáȟtagya or Maȟpíya Íyapat'o) (c. 1838 – September 5, 1905) was a chief of the ''Minneconjou'' Teton Lakota (also known as Sioux) known for his bravery and skill in battle, physical strength and d ...

). He saved Crazy Horse's life at least once and was with him when he died.

Rattling Blanket Woman or Tȟašína Ȟlaȟlá Wiŋ (1814–1844) was the daughter of Black Buffalo and White Cow (also known as Iron Cane). Her older siblings were Lone Horn

Lone Horn (Lakota: Hewáŋžiča, or in historical spelling "Heh-won-ge-chat" or "Ha-wón-je-tah"), also called One Horn (1790 –1877), born in present-day South Dakota, was chief of the Wakpokinyan (Flies Along the Stream) band of the Minnec ...

(born 1790, died 1877) and Good Looking Woman (born 1810). Her younger sister was named Looks At It (born 1815), later given the name They Are Afraid of Her. The historian George Hyde wrote that Rattling Blanket Woman was Miniconjou

The Miniconjou (Lakota: Mnikowoju, Hokwoju – ‘Plants by the Water’) are a Native American people constituting a subdivision of the Lakota people, who formerly inhabited an area in western present-day South Dakota from the Black Hills i ...

and the sister of Spotted Tail

Spotted Tail (Siŋté Glešká pronounced ''gleh-shka''; birth name T'at'aŋka Napsíca "Jumping Buffalo"Ingham (2013) uses 'c' to represent 'č'. ); born c. 1823 – died August 5, 1881) was a Brulé Lakota tribal chief. Although a great warr ...

, who became a Brulé

The Brulé are one of the seven branches or bands (sometimes called "sub-tribes") of the Teton (Titonwan) Lakota American Indian people. They are known as Sičhą́ǧu Oyáte (in Lakȟóta) —Sicangu Oyate—, ''Sicangu Lakota, o''r "Burnt ...

head chief. She may have been a member of either of the One Horn or Lone Horn

Lone Horn (Lakota: Hewáŋžiča, or in historical spelling "Heh-won-ge-chat" or "Ha-wón-je-tah"), also called One Horn (1790 –1877), born in present-day South Dakota, was chief of the Wakpokinyan (Flies Along the Stream) band of the Minnec ...

families, leaders of the Miniconjou

The Miniconjou (Lakota: Mnikowoju, Hokwoju – ‘Plants by the Water’) are a Native American people constituting a subdivision of the Lakota people, who formerly inhabited an area in western present-day South Dakota from the Black Hills i ...

. She was said to be beautiful and a fast runner.

In 1844, while out hunting buffalo, Waglula helped defend a Lakota village under attack by the Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus ''Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifical ...

. In gratitude he gave Waglula his two eldest daughters as wives: Iron Between Horns (age 18) and Kills Enemy (age 17). Corn's youngest daughter, Red Leggins, who was 15 at the time, requested to go with her sisters; all became Waglula's wives. When Waglula returned with the new wives, Rattling Blanket Woman, who had been unsuccessful in conceiving another child, thought she had lost favor with her husband and hanged herself. Waglula went into mourning for four years. Rattling Blanket Woman's sister, Good Looking Woman, came to offer herself as a replacement wife, and stayed on to raise Crazy Horse. Other versions of the legend posit that she was grief-stricken by the deaths of those she knew; that her husband accused her of running off with her brother-in-law; or that she had had affair with a European-American man.

According to Frederick Hoxie's ''Encyclopedia of North American Indians'', Crazy Horse was the third in his male line to bear the name of Crazy Horse. The love of his life was Tȟatȟáŋkasápawiŋ (Black Buffalo Woman), whom he courted, but she married another man named Mní Níča (No Water). At one point, Crazy Horse persuaded Black Buffalo Woman to run away with him. No Water borrowed a pistol and ran after his wife. When he found her with Crazy Horse, he fired at him, injuring him in the face and leaving a noticeable scar. Crazy Horse was married two times, first to Tȟašinásápawiŋ (Black Shawl) and second to Nellie Larrabee (Laravie). Nellie Larrabee was given the task of spying on Crazy Horse for the military, so the marriage is suspect. Only Black Shawl bore him any children, a daughter named Kȟokípȟapiwiŋ (They Are Afraid of Her), who died at age three.

Visions

Crazy Horse lived in a Lakota camp in present-dayWyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

with his younger half-brother, Little Hawk

Little Hawk ( Lakota: Čhetáŋ Čík’ala) (1836–1900) was an Oglala Lakota war chief and a half-brother of Worm, father of Crazy Horse ( Lakota: Tashunka-witko)....

Family

Little Hawk was born about 1836. His father was the holy man vari ...

, son of Iron Between Horns and Waglula. Little Hawk was the nephew of his maternal step-grandfather, Long Face, and a cousin, High Horse. In 1854, the camp was entered by Lieutenant John Lawrence Grattan

John Lawrence Grattan (June 1, 1830 – August 19, 1854) was a mid-19th century US Cavalry officer, whose poor judgement and inexperience led to the Grattan massacre, which was a major instigator for the First Sioux War.

Early life and militar ...

and 29 other U.S. troopers, who intended to arrest a Miniconjou man for having stolen a cow. The cow had wandered into the camp, and after a short time someone butchered it and passed the meat out among the people. When the soldiers fatally shot Chief Conquering Bear

Matȟó Wayúhi ("Conquering Bear") ( 1800 – August 19, 1854) was a Brulé Lakota chief who signed the Fort Laramie Treaty (1851). He was killed in 1854 when troops from Fort Laramie entered his encampment to arrest a Sioux who had shot a cal ...

, the Lakota returned fire, killing all 30 soldiers and a civilian interpreter in what was later called the Grattan massacre.''The Authorized Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part Two: Defending the Homeland Prior to the 1868 Treaty'', DVD William Matson and Mark Frethem, Producers. Reelcontact.com Productions, 2007.

After witnessing the death of Conquering Bear at the Grattan massacre, Crazy Horse began to get trance

Trance is a state of semi-consciousness in which a person is not self-aware and is either altogether unresponsive to external stimuli (but nevertheless capable of pursuing and realizing an aim) or is selectively responsive in following the dir ...

visions. Curly went out on a vision quest

A vision quest is a rite of passage in some Native American cultures. It is usually only undertaken by young males entering adulthood.

Individual Indigenous cultures have their own names for their rites of passage. "Vision quest" is an English- ...

to seek guidance but without going through the traditional procedures first. In his vision, a warrior on his horse rode out of a lake and the horse seemed to float and dance throughout the vision. He wore simple clothing, no face paint, his hair down with just a feather in it, and a small brown stone behind his ear. Bullets and arrows flew around him as he charged forward, but neither he nor his horse was hit. A thunderstorm came over the warrior, and his people grabbed hold of his arms trying to hold him back. The warrior broke their hold and then lightning struck him, leaving a lightning symbol on his cheek, and white marks like hailstones appeared on his body. The warrior told Curly that as long he dressed modestly, his tribesmen did not touch him, and he did not take any scalps or war trophies, then he would not be harmed in battle. As the vision ended, he heard a red-tailed hawk shrieking off in the distance. Curly’s father later interpreted the vision and said that the warrior was going to be him. The lightning bolt on his cheek and the hailstones on his body were to become his war paint. Curly was to follow the warrior’s role to dress modestly and to do as the warrior's prophecy said so he would be unharmed in battle. For the most part, the vision was true and Crazy Horse was rarely harmed in battle, except for when he was struck by an arrow after taking two enemy scalps. He was shot in the face by No Water when Little Big Man tried to hold Crazy Horse back to prevent a fight from breaking out, and he was held back by one of his tribesmen—according to some reports, Little Big Man himself—when he was stabbed by a bayonet the night he died.

His father ''Waglula'' took him to what today is Sylvan Lake, South Dakota, where they both sat to do a ''hemblecha'' or vision quest. A red-tailed hawk led them to their respective spots in the hills; as the trees are tall in the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black Elk P ...

, they could not always see where they were going. Crazy Horse sat between two humps at the top of a hill north and to the east of the lake. Waglula sat south of Black Elk Peak

Black Elk Peak is the highest natural point in the U.S. state of South Dakota and the Midwestern United States. It lies in the Black Elk Wilderness area, in southern Pennington County, in the Black Hills National Forest. The peak lies west-sout ...

but north of his son.

Crazy Horse's vision first took him to the South where, in Lakota spirituality, one goes upon death. He was brought back and was taken to the West in the direction of the ''wakiyans'' (thunder beings). He was given a medicine bundle

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

to protect him for life. One of his animal protectors would be the white owl which, according to Lakota spirituality, would give extended life. He was also shown his "face paint" for battle, to consist of a yellow lightning bolt down the left side of his face, and white powder. He would wet this and put marks over his vulnerable areas; when dried, the marks looked like hailstones

Hail is a form of solid precipitation. It is distinct from ice pellets (American English "sleet"), though the two are often confused. It consists of balls or irregular lumps of ice, each of which is called a hailstone. Ice pellets generally fa ...

. His face paint was similar to that of his father, who used a red lightning strike down the right side of his face and three red hailstones on his forehead. Crazy Horse put no make-up on his forehead and did not wear a war bonnet. Lastly, he was given a sacred song that is still sung by the Oglala people today and he was told he would be a protector of his people.

Black Elk

Heȟáka Sápa, commonly known as Black Elk (December 1, 1863 – August 19, 1950), was a ''wičháša wakȟáŋ'' ("medicine man, holy man") and ''heyoka'' of the Oglala Lakota people. He was a second cousin of the war leader Crazy Horse and f ...

, a contemporary and cousin of Crazy Horse, related the vision in '' Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux'', from talks with John G. Neihardt:

Crazy Horse received a black stone from a medicine man named Horn Chips to protect his horse, a black-and-white pinto

Pinto is a Portuguese language, Portuguese, Spanish language, Spanish, Sephardi Jews, Jewish (Sephardic), and Italian language, Italian surname. It is a high-frequency surname in all List of countries and territories where Portuguese is an officia ...

he named ''Inyan'' (rock or stone). He placed the stone behind the horse's ear so that the medicine from his vision quest and Horn Chips would combine—he and his horse would be one in battle. The more accepted account, however, is that Horn Chips gave Crazy Horse a sacred stone that protected him from bullets. Subsequently, Crazy Horse was never wounded by a bullet. In addition, "Horn Chips" is not the correct name of this medicine man, though it has become a repeated error since its first publication in 1982. His Lakota name was ''Woptura'', and he was given the name "Chips" by the government and was referred to as Old Man Chips. Horn Chips was one of his sons, who was also known as Charles Chips.

Personality

Crazy Horse was known to have a personality characterized by aloofness, shyness, modesty and lonesomeness. He was generous to the poor, the elderly, and children. In ''Black Elk Speaks,'' Neihardt relays:War leadership

Title of "Shirt Wearer"

Through the late 1850s and early 1860s, Crazy Horse's reputation as a warrior grew, as did his fame among the Lakota. The Lakota told accounts of him in their oral histories. His first kill was aShoshone

The Shoshone or Shoshoni ( or ) are a Native American tribe with four large cultural/linguistic divisions:

* Eastern Shoshone: Wyoming

* Northern Shoshone: southern Idaho

* Western Shoshone: Nevada, northern Utah

* Goshute: western Utah, easter ...

raider who had murdered a Lakota woman washing buffalo meat along the Powder River. Crazy Horse fought in numerous battles between the Lakota and their traditional enemies, the Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus ''Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifical ...

, Shoshone

The Shoshone or Shoshoni ( or ) are a Native American tribe with four large cultural/linguistic divisions:

* Eastern Shoshone: Wyoming

* Northern Shoshone: southern Idaho

* Western Shoshone: Nevada, northern Utah

* Goshute: western Utah, easter ...

, Pawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska

* ...

, Blackfeet

The Blackfeet Nation ( bla, Aamsskáápipikani, script=Latn, ), officially named the Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana, is a federally recognized tribe of Siksikaitsitapi people with an Indian reservation in Monta ...

, and Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

, among Plains tribes.

In 1864, after the ''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

Third Colorado Cavalry

The 3rd Colorado Cavalry Regiment was a Union Army unit formed in the mid-1860s when increased traffic on the United States emigrant trails and settler encroachment resulted in numerous attacks against them by the Cheyenne and Arapaho. The Hung ...

decimated Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enroll ...

and Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho band ...

in the Sand Creek Massacre, Oglala and Minneconjou bands allied with them against the U.S. military. Crazy Horse was present at the Battle of Platte Bridge

The Battle of Platte Bridge, also called the Battle of Platte Bridge Station, on July 26, 1865, was the culmination of a summer offensive by the Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne Indians against the United States army. In May and June the Indians raid ...

and the Battle of Red Buttes in July 1865. Because of his fighting ability and for his generosity to the tribe, in 1865 Crazy Horse was named an ''Ogle Tanka Un'' ("Shirt Wearer", or war leader) by the tribe.

Battle of the Hundred in the Hand (Fetterman Fight)

On December 21, 1866, Crazy Horse and six other warriors, both Lakota and Cheyenne, decoyed Capt.William Fetterman

William Judd Fetterman (1833 – December 21, 1866) was an officer in the United States Army during the American Civil War and the subsequent Red Cloud's War on the Great Plains. Fetterman and his command of 80 men were killed in the Fetterm ...

's 53 infantrymen and 27 cavalry troopers under Lt. Grummond into an ambush. They had been sent out from Fort Phil Kearny

Fort Phil Kearny was an outpost of the United States Army that existed in the late 1860s in present-day northeastern Wyoming along the Bozeman Trail. Construction began in 1866 on Friday, July 13, by Companies A, C, E, and H of the 2nd Battalion, ...

to follow up on an earlier attack on a wood train. Crazy Horse lured Fetterman's infantry up a hill. Grummond's cavalry followed the other six decoys along Peno Head Ridge and down toward Peno Creek, where several Cheyenne women taunted the soldiers. Meanwhile, Cheyenne leader Little Wolf

Little Wolf (''Cheyenne'': ''Ó'kôhómôxháahketa'', sometimes transcribed ''Ohcumgache'' or ''Ohkomhakit'', more correctly translated Little Coyote, 18201904) was a Northern Só'taeo'o Chief and Sweet Medicine Chief of the Northern Cheyenne. ...

and his warriors, who had been hiding on the opposite side of Peno Head Ridge, blocked the return route to the fort. The Lakota warriors swept over the hill and attacked the infantry. Additional Cheyenne and Lakota hiding in the buckbrush along Peno Creek effectively surrounded the soldiers. Seeing that they were surrounded, Grummond headed his cavalry back to Fetterman.

The combined warrior forces of nearly 1,000 killed all the US soldiers in what became known at the time to the white population as the Fetterman Massacre

The Fetterman Fight, also known as the Fetterman Massacre or the Battle of the Hundred-in-the-Hands or the Battle of a Hundred Slain, was a battle during Red Cloud's War on December 21, 1866, between a confederation of the Lakota, Cheyenne, and ...

. It was the Army's worst defeat on the Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

up to that time. The Lakota and Cheyenne call it the Battle of the Hundred in the Hand.. Joseph M. Marshall III, ''The Journey of Crazy Horse'', Penguin Books 2004.

Wagon Box Fight

On August 2, 1867, Crazy Horse participated in the Wagon Box Fight, also near Fort Phil Kearny. Lakota forces numbering between 1000 and 2000 attacked a wood-cutting crew near the fort. Most of the soldiers fled to a circle of wagon boxes without wheels, using them for cover as they fired at the Lakota. The Lakota took substantial losses, as the soldiers were firing new breech-loading rifles. These could fire ten times a minute compared to the oldmuzzle-loading

A muzzleloader is any firearm into which the projectile and the propellant charge is loaded from the muzzle of the gun (i.e., from the forward, open end of the gun's barrel). This is distinct from the modern (higher tech and harder to make) design ...

rate of three times a minute. The Lakota charged after the soldiers fired the first time, expecting the delay of their older muskets before being able to fire again. The soldiers suffered only five killed and two wounded while the Lakota suffered between 50 and 120 casualties. Many Lakota were buried in the hills surrounding Fort Phil Kearny

Fort Phil Kearny was an outpost of the United States Army that existed in the late 1860s in present-day northeastern Wyoming along the Bozeman Trail. Construction began in 1866 on Friday, July 13, by Companies A, C, E, and H of the 2nd Battalion, ...

in Wyoming.

Controversy over Black Buffalo Woman

In the fall of 1870, Crazy Horse invited Black Buffalo Woman to accompany him on a buffalo hunt in the Slim Buttes area of present-day northwestern South Dakota. She was the wife of No Water, who had a reputation for drinking too much. It was Lakota custom to allow a woman to divorce her husband at any time. She did so by moving in with relatives or with another man, or by placing the husband's belongings outside their lodge. Although some compensation might be required to smooth over hurt feelings, the rejected husband was expected to accept his wife's decision. No Water was away from camp when Crazy Horse and Black Buffalo Woman left for the buffalo hunt. No Water tracked down Crazy Horse and Black Buffalo Woman in the Slim Buttes area. When he found them in ateepee

A tipi , often called a lodge in English, is a conical tent, historically made of animal hides or pelts, and in more recent generations of canvas, stretched on a framework of wooden poles. The word is Siouan, and in use in Dakhótiyapi, Lakȟó ...

, he called Crazy Horse's name from outside. When Crazy Horse answered, No Water stuck a pistol into the teepee and aimed for Crazy Horse. Touch the Clouds

Touch the Clouds (Lakota: Maȟpíya Ičáȟtagya or Maȟpíya Íyapat'o) (c. 1838 – September 5, 1905) was a chief of the ''Minneconjou'' Teton Lakota (also known as Sioux) known for his bravery and skill in battle, physical strength and d ...

, Crazy Horse's first cousin and son of Lone Horn

Lone Horn (Lakota: Hewáŋžiča, or in historical spelling "Heh-won-ge-chat" or "Ha-wón-je-tah"), also called One Horn (1790 –1877), born in present-day South Dakota, was chief of the Wakpokinyan (Flies Along the Stream) band of the Minnec ...

, was sitting in the teepee nearest the entry. He knocked the pistol upward as No Water fired, deflecting the bullet to Crazy Horse's upper jaw. No Water left, with Crazy Horse's relatives in hot pursuit. No Water ran his horse until it died and continued on foot until he reached the safety of his own village.

Several elders convinced Crazy Horse and No Water that no more blood should be shed. As compensation for the shooting, No Water gave Crazy Horse three horses. Because Crazy Horse was with a married woman, he was stripped of his title as Shirt Wearer (leader).

Black Shawl and Nellie Larrabee

Crazy Horse marriedBlack Shawl

Black Shawl or Tasina Sapewin was the wife of Crazy Horse, whom she married in 1871. She was Crazy Horse's second wife. She was a member of the Oglala Lakota and relative of Spotted Tail. She was the sister of Red Feather.

The elders sent Black ...

, a member of the Oglala Lakota and relative of Spotted Tail

Spotted Tail (Siŋté Glešká pronounced ''gleh-shka''; birth name T'at'aŋka Napsíca "Jumping Buffalo"Ingham (2013) uses 'c' to represent 'č'. ); born c. 1823 – died August 5, 1881) was a Brulé Lakota tribal chief. Although a great warr ...

. The elders sent her to heal Crazy Horse after his altercation with No Water. Crazy Horse and Black Shawl Woman were married in 1871. Black Shawl gave birth to Crazy Horse's only child, a daughter named They Are Afraid Of Her, who died in 1873. Black Shawl outlived Crazy Horse. She died in 1927 during the influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

outbreaks of the 1920s.

Red Cloud also arranged to send a young woman, Nellie Larrabee, to live in Crazy Horse's lodge. Interpreter William Garnett described Larrabee as "a half-blood, not of the best frontier variety, an invidious and evil woman". Larrabee, also referred to as Chi-Chi and Brown Eyes Woman, was the daughter of a French trader and a Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enroll ...

woman. Garnett's first-hand account of Crazy Horse's surrender alludes to Larrabee as the "half blood woman" who caused Crazy Horse to fall into a "domestic trap which insensibly led him by gradual steps to his destruction."

Great Sioux War of 1876–77

On June 17, 1876, Crazy Horse led a combined group of approximately 1,500 Lakota and Cheyenne in a surprise attack against brevetted Brigadier GeneralGeorge Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan ...

's force of 1,000 cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

and infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

, and allied 300 Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus ''Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifical ...

and Shoshone

The Shoshone or Shoshoni ( or ) are a Native American tribe with four large cultural/linguistic divisions:

* Eastern Shoshone: Wyoming

* Northern Shoshone: southern Idaho

* Western Shoshone: Nevada, northern Utah

* Goshute: western Utah, easter ...

warriors in the Battle of the Rosebud

The Battle of the Rosebud (also known as the Battle of Rosebud Creek) took place on June 17, 1876, in the Montana Territory between the United States Army and its Crow and Shoshoni allies against a force consisting mostly of Lakota Sioux and Nort ...

. The battle, although not substantial in terms of human losses, delayed Crook's joining the 7th Cavalry under George A. Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

. It contributed to Custer’s subsequent defeat at the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

.

A week later at 3:00 p.m. on June 25, 1876, Custer's 7th Cavalry attacked a large encampment of Cheyenne and Lakota bands along the Little Bighorn River, marking the beginning of his last battle. Crazy Horse's actions during the battle are unknown.

Hunkpapa warriors led by Chief Gall

Gall (c. 1840 – December 5, 1894), Lakota ''Phizí'', was an important military leader of the Hunkpapa Lakota in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. He spent four years in exile in Canada with Sitting Bull's people, after the wars ended and surre ...

led the main body of the attack. Crazy Horse's tactical and leadership role in the battle remains ambiguous. While some historians think that Crazy Horse led a flanking assault, ensuring the death of Custer and his men, the only proven fact is that Crazy Horse was a major participant in the battle. His personal courage was attested to by several eye-witness Indian accounts. Water Man, one of only five Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho band ...

warriors who fought, said Crazy Horse "was the bravest man I ever saw. He rode closest to the soldiers, yelling to his warriors. All the soldiers were shooting at him, but he was never hit." Sioux battle participant Little Soldier said, "The greatest fighter in the whole battle was Crazy Horse." Crazy Horse is said to have exhorted his warriors before the fight with the battle cry "Hóka-héy! Today is a good day to die!" but the quotation is inaccurately attributed. The earliest published reference is from 1881, in which the phrase is attributed to Low Dog

''Low Dog'' (Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, se ...

. The English version is not an accurate translation from the Lakota language, "Hóka-héy!" Both phrases are used in context by Black Elk in Black Elk Speaks

''Black Elk Speaks'' is a 1932 book by John G. Neihardt, an American poet and writer, who relates the story of Black Elk, an Oglala Lakota medicine man. Black Elk spoke in Lakota and Black Elk's son, Ben Black Elk, who was present during the tal ...

.

On September 10, 1876, Captain Anson Mills

Anson Mills (August 31, 1834 – November 5, 1924) was a United States Army officer, surveyor, inventor, and entrepreneur. Engaged in south Texas as a land surveyor and civil engineer, he both named and laid out the city of El Paso, Texas. Mills a ...

and two battalions of the Third Cavalry captured a Miniconjou

The Miniconjou (Lakota: Mnikowoju, Hokwoju – ‘Plants by the Water’) are a Native American people constituting a subdivision of the Lakota people, who formerly inhabited an area in western present-day South Dakota from the Black Hills i ...

village of 36 tipis in the Battle of Slim Buttes

The Battle of Slim Buttes was fought on September 9–10, 1876, in the Great Sioux Reservation between the United States Army and Miniconjou Sioux during the Great Sioux War of 1876. It marked the first significant victory for the army sinc ...

, South Dakota. Crazy Horse and his followers attempted to rescue the camp and its headman, (Old Man) American Horse, but they were unsuccessful. The soldiers killed American Horse and much of his family after they holed up in a cave for several hours.

On January 8, 1877, Crazy Horse's warriors fought their last major battle at Wolf Mountain, against the US Cavalry

The United States Cavalry, or U.S. Cavalry, was the designation of the mounted force of the United States Army by an act of Congress on 3 August 1861.Price (1883) p. 103, 104 This act converted the U.S. Army's two regiments of dragoons, one r ...

in the Montana Territory

The Territory of Montana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1864, until November 8, 1889, when it was admitted as the 41st state in the Union as the state of Montana.

Original boundaries

T ...

. His people struggled through the winter, weakened by hunger and the long cold. Crazy Horse decided to surrender with his band to protect them, and went to Fort Robinson

Fort Robinson is a former U.S. Army fort and now a major feature of Fort Robinson State Park, a public recreation and historic preservation area located west of Crawford on U.S. Route 20 in the Pine Ridge region of northwest Nebraska.

The for ...

in Nebraska.

Last Sun Dance of 1877

The Last Sun Dance of 1877 is significant in Lakota history as the Sun Dance held to honor Crazy Horse one year after the victory at theBattle of the Little Big Horn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nort ...

, and to offer prayers for him in the trying times ahead. Crazy Horse attended the Sun Dance as the honored guest but did not take part in the dancing. Five warrior cousins sacrificed blood and flesh for Crazy Horse at the Last Sun Dance of 1877. The five warrior cousins were three brothers, Flying Hawk

Flying Hawk (Oglala Lakota: ''Čhetáŋ Kiŋyáŋ'' in Standard Lakota Orthography; also known as Moses Flying Hawk; March 1854 – December 24, 1931) was an Oglala Lakota warrior, historian, educator and philosopher. Flying Hawk's life chron ...

, Kicking Bear

Kicking Bear ( lkt, Matȟó Wanáȟtaka, March 18, 1845 – May 28, 1904) was an Oglala Lakota who became a band chief of the Miniconjou Lakota Sioux. He fought in several battles with his brother, Flying Hawk, and first cousin, Crazy Horse, dur ...

and Black Fox II, all sons of Chief Black Fox, also known as Great Kicking Bear, and two other cousins, Eagle Thunder and Walking Eagle. The five warrior cousins were braves considered vigorous battle men of distinction.

Surrender and death

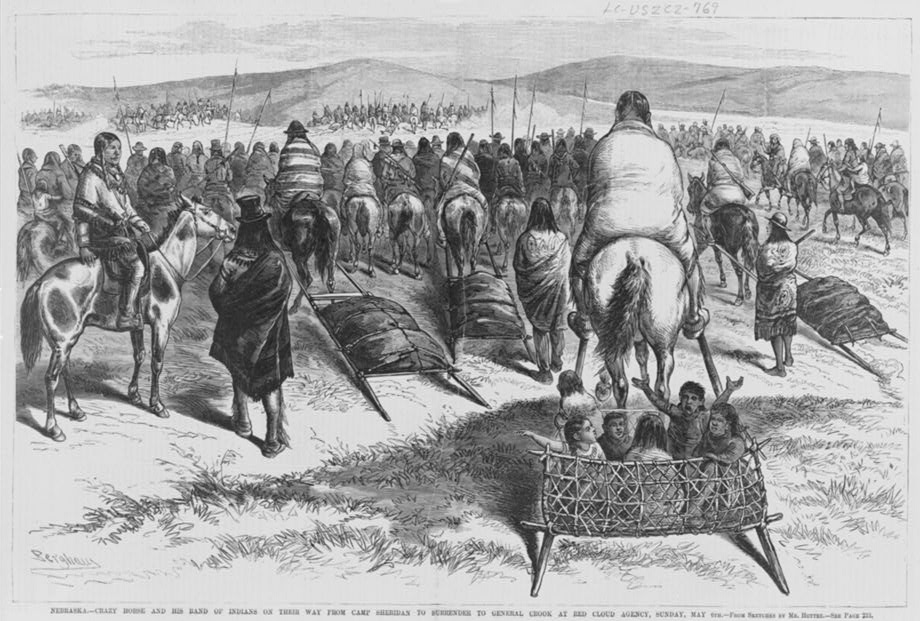

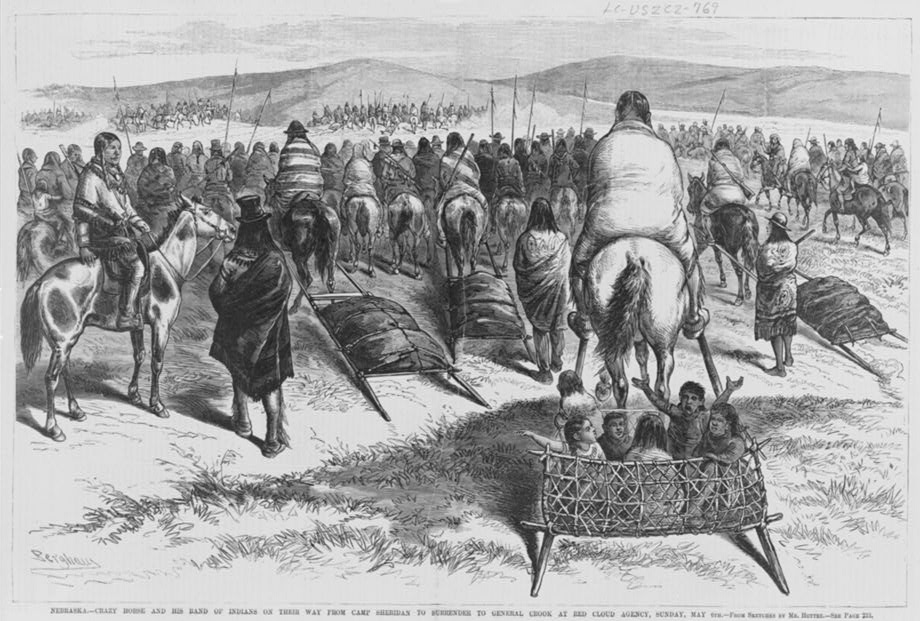

Crazy Horse and other northernOglala

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota, make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority of the Oglala live o ...

leaders arrived at the Red Cloud Agency

The Red Cloud Agency was an Indian agency for the Oglala Lakota as well as the Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho, from 1871 to 1878. It was located at three different sites in Wyoming Territory and Nebraska before being moved to South Dakota. It w ...

, located near Fort Robinson

Fort Robinson is a former U.S. Army fort and now a major feature of Fort Robinson State Park, a public recreation and historic preservation area located west of Crawford on U.S. Route 20 in the Pine Ridge region of northwest Nebraska.

The for ...

, Nebraska, on May 5, 1877. Together with He Dog

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

, Little Big Man

Little Big Man ( Lakota: Wičháša Tȟáŋkala), or Charging Bear, was an Oglala Lakota, or Oglala Sioux, who was a fearless and respected warrior who fought under, and was distant cousin to, Crazy Horse ("His-Horse-Is-Crazy"). He opposed the 186 ...

, Iron Crow and others, they met in a solemn ceremony with First Lieutenant William P. Clark as the first step in their formal surrender.

For the next four months, Crazy Horse resided in his village near the Red Cloud Agency

The Red Cloud Agency was an Indian agency for the Oglala Lakota as well as the Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho, from 1871 to 1878. It was located at three different sites in Wyoming Territory and Nebraska before being moved to South Dakota. It w ...

. The attention that Crazy Horse received from the Army drew the jealousy of Red Cloud

Red Cloud ( lkt, Maȟpíya Lúta, italic=no) (born 1822 – December 10, 1909) was a leader of the Oglala Lakota from 1868 to 1909. He was one of the most capable Native American opponents whom the United States Army faced in the western ...

and Spotted Tail

Spotted Tail (Siŋté Glešká pronounced ''gleh-shka''; birth name T'at'aŋka Napsíca "Jumping Buffalo"Ingham (2013) uses 'c' to represent 'č'. ); born c. 1823 – died August 5, 1881) was a Brulé Lakota tribal chief. Although a great warr ...

, two Lakota who had long before come to the agencies and adopted the white ways. Rumors of Crazy Horse's desire to slip away and return to the old ways of life started to spread at the Red Cloud and Spotted Tail agencies. In August 1877 officers at Camp Robinson received word that the Nez Perce

The Nez Percé (; autonym in Nez Perce language: , meaning "we, the people") are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who are presumed to have lived on the Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest region for at least 11,500 years.Ames, K ...

of Chief Joseph

''Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt'' (or ''Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it'' in Americanist orthography), popularly known as Chief Joseph, Young Joseph, or Joseph the Younger (March 3, 1840 – September 21, 1904), was a leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa ...

had broken out of their reservation in Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

and were fleeing north through Montana toward Canada. When asked by Lieutenant Clark to join the Army against the Nez Perce, Crazy Horse and the Miniconjou

The Miniconjou (Lakota: Mnikowoju, Hokwoju – ‘Plants by the Water’) are a Native American people constituting a subdivision of the Lakota people, who formerly inhabited an area in western present-day South Dakota from the Black Hills i ...

leader Touch the Clouds objected, saying that they had promised to remain at peace when they surrendered. According to one version of events, Crazy Horse finally agreed, saying that he would fight "till all the Nez Perce were killed." But his words were apparently misinterpreted by a half-Tahitian scout, Frank Grouard

Frank Benjamin Grouard (also known as Frank Gruard and Benjamin Franklin Grouard) (September 20, 1850 – August 15, 1905) was a Scout and interpreter for General George Crook during the American Indian War of 1876. For the better part of ...

, a person not to be confused with Fred Gerard

Fredric Frances Gerard (November 14, 1829 – January 30, 1913) was a frontiersman, army scout, and civilian interpreter for George Armstrong Custer's 7th U.S. Cavalry during the Little Bighorn Campaign.

Early life

Fred Gerard was born in S ...

, another U.S. Cavalry

The United States Cavalry, or U.S. Cavalry, was the designation of the mounted force of the United States Army by an act of Congress on 3 August 1861.Price (1883) p. 103, 104 This act converted the U.S. Army's two regiments of dragoons, one r ...

scout during the summer of 1876. Grouard reported that Crazy Horse had said that he would "go north and fight until not a white man is left." When he was challenged over his interpretation, Grouard left the council. Another interpreter, William Garnett, was brought in but quickly noted the growing tension.

With the growing trouble at the Red Cloud Agency, General George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan ...

was ordered to stop at Fort Robinson. A council of the Oglala leadership was called, then canceled, when Crook was incorrectly informed that Crazy Horse had said the previous evening that he intended to kill the general during the proceedings. Crook ordered Crazy Horse's arrest and then departed; leaving the post commander at Fort Robinson, Lieutenant Colonel Luther P. Bradley

Luther Prentice Bradley (December 8, 1822 – March 13, 1910) was an American soldier who served as a Union general officer during the American Civil War.

Early life

Bradley was born in New Haven, Connecticut on December 8, 1822. He held vari ...

, to carry out his order. Additional troops were brought in from Fort Laramie. On the morning of September 4, 1877, two columns moved against Crazy Horse's village, only to find that it had scattered during the night. Crazy Horse had fled to the nearby Spotted Tail Agency with his wife, who had become ill with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

. After meeting with military officials at Camp Sheridan, the adjacent military post, Crazy Horse agreed to return to Fort Robinson with Lieutenant Jesse M. Lee, the Indian agent at Spotted Tail.

On the morning of September 5, 1877, Crazy Horse and Lieutenant Lee, accompanied by Touch the Clouds as well as a number of Indian scouts, departed for Fort Robinson. Arriving that evening outside the adjutant's office, Lieutenant Lee was informed that he was to turn Crazy Horse over to the Officer of the Day. Lee protested and hurried to Bradley's quarters to debate the issue, but without success. Bradley had received orders that Crazy Horse was to be arrested and taken under the cover of darkness to Division Headquarters. Lee turned the Oglala war chief over to Captain James Kennington, in charge of the post guard, who accompanied Crazy Horse to the post guardhouse. Once inside, Crazy Horse struggled with the guard and Little Big Man and attempted to escape. Just outside the door, Crazy Horse was stabbed with a bayonet by one of the members of the guard. He was taken to the adjutant's office, where he was tended by the assistant post surgeon at the post, Valentine McGillycuddy

Valentine Trant McGillycuddy (February 14, 1849 – June 6, 1939) was a surgeon who served with expeditions and United States military forces in the West. He was considered controversial for his efforts to build a sustainable relationship betw ...

, and died late that night.

The following morning, Crazy Horse's body was turned over to his elderly parents, who took it to Camp Sheridan and placed it on a burial scaffold. The following month, when the Spotted Tail Agency was moved to the Missouri River, Crazy Horse's parents moved the remains to an undisclosed location. There are at least four possible locations as noted on a state highway memorial near Wounded Knee, South Dakota

Wounded Knee ( lkt, Čaŋkpé Opí) is a census-designated place (CDP) on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in Oglala Lakota County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 364 at the 2020 census.

The town is named for the Wounded Knee Cr ...

. His final resting place remains unknown.

Controversy over his death

John Gregory Bourke

John Gregory Bourke (; June 23, 1846 – June 8, 1896) was a captain in the United States Army and a prolific diarist and postbellum author; he wrote several books about the American Old West, including ethnologies of its indigenous peoples. He ...

's memoir of his service in the Indian wars, ''On the Border with Crook'', describes a different account of Crazy Horse's death. He based his account on an interview with Crazy Horse's rival, Little Big Man, who was present at Crazy Horse's arrest and fatal wounding. The interview took place over a year after Crazy Horse's death. Little Big Man said that, as Crazy Horse was being escorted to the guardhouse, he suddenly pulled two knives from under his blanket and held one in each hand. One knife was reportedly fashioned from an army bayonet. Little Big Man, standing behind him, seized Crazy Horse by both elbows, pulling his arms up behind him. As Crazy Horse struggled, Little Big Man lost his grip on one elbow, and Crazy Horse drove his own knife deep into his own lower back. The guard stabbed Crazy Horse with his bayonet in the back, who then fell and surrendered to the guards.

When Bourke asked about the popular account of the guard bayoneting Crazy Horse first, Little Big Man said that the guard had thrust with his bayonet, but that Crazy Horse's struggles resulted in the guard's thrust missing entirely and lodging his bayonet into the frame of the guardhouse door. Little Big Man said that in the hours immediately following Crazy Horse's wounding, the camp commander had suggested the story of the guard being responsible to hide Little Big Man's role in the death of Crazy Horse and avoid any inter-clan reprisals.

Little Big Man's account is questionable; it is the only one of 17 eyewitness sources (from Lakota, US Army, and "mixed-blood

The term mixed-blood in the United States and Canada has historically been described as people of multiracial backgrounds, in particular mixed European and Native American ancestry. Today, the term is often seen as pejorative.

Northern Woodla ...

" individuals) that fails to attribute Crazy Horse's death to a soldier at the guardhouse. The author Thomas Powers

Thomas Powers (born December 12, 1940 in New York City) is an American author and intelligence expert.

He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting in 1971 together with Lucinda Franks for his articles on Weatherman member Diana Ough ...

cites various witnesses who said Crazy Horse was fatally wounded when his back was pierced by a guard's bayonet.

The identity of the soldier responsible for the bayoneting of Crazy Horse is also debated. Only one eyewitness account actually identifies the soldier as Private William Gentles

William Gentles (c.1830–1878) was a private in the U.S. Army who is generally acknowledged as the soldier who bayoneted the Oglala war leader Crazy Horse in 1877.

Early life

William Gentles was born in County Tyrone, Ireland. The exact date ...

. Historian Walter M. Camp circulated copies of this account to individuals who had been present who questioned the identity of the soldier and provided two additional names. To this day, the identification remains questioned.

Photograph controversy

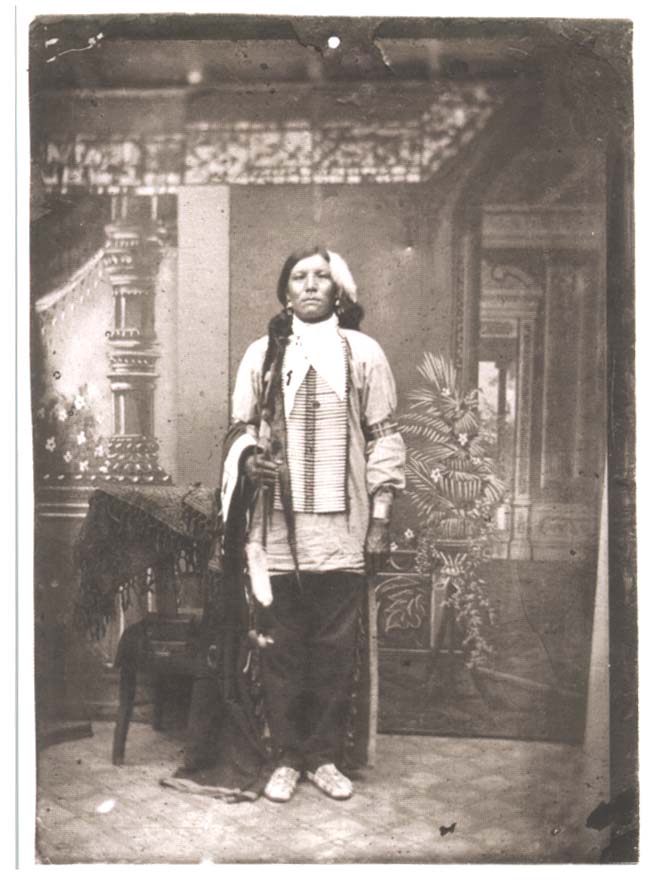

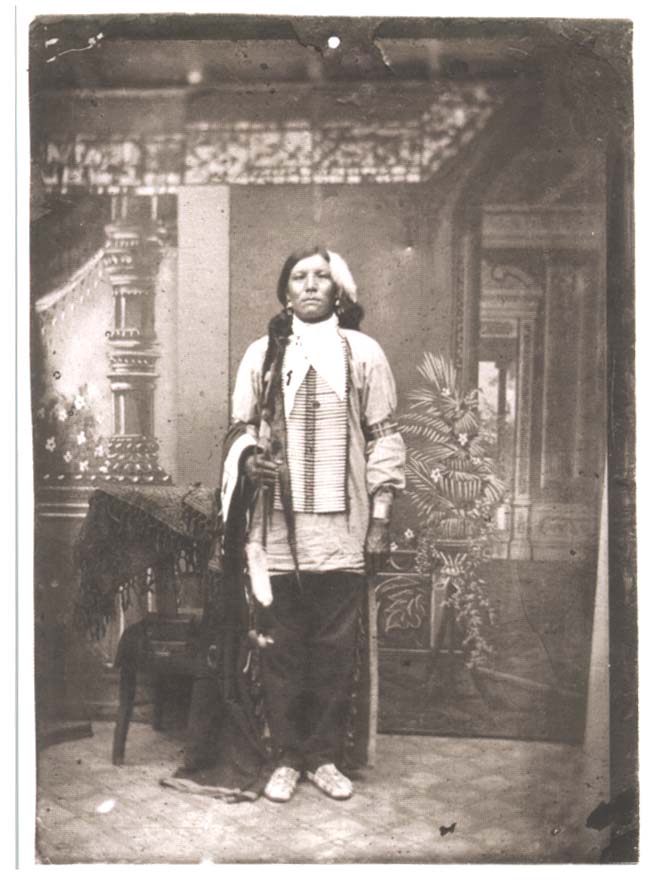

Most sources question whether Crazy Horse was ever photographed.

Most sources question whether Crazy Horse was ever photographed. Valentine McGillycuddy

Valentine Trant McGillycuddy (February 14, 1849 – June 6, 1939) was a surgeon who served with expeditions and United States military forces in the West. He was considered controversial for his efforts to build a sustainable relationship betw ...

doubted any photograph of the war leader had been taken. In 1908, Walter Camp

Walter Chauncey Camp (April 7, 1859 – March 14, 1925) was an American football player, coach, and sports writer known as the "Father of American Football". Among a long list of inventions, he created the sport's line of scrimmage and the system ...

wrote to the agent for the Pine Ridge Reservation

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation ( lkt, Wazí Aháŋhaŋ Oyáŋke), also called Pine Ridge Agency, is an Oglala Lakota Indian reservation located entirely within the U.S. state of South Dakota. Originally included within the territory of the Grea ...

inquiring about a portrait. "I have never seen a photo of Crazy Horse," Agent Brennan replied, "nor am I able to find any one among our Sioux here who remembers having seen a picture of him. Crazy Horse had left the hostiles but a short time before he was killed and it's more than likely he never had a picture taken of himself."

In 1956, a small tintype

A tintype, also known as a melainotype or ferrotype, is a photograph made by creating a direct positive on a thin sheet of metal coated with a dark lacquer or enamel and used as the support for the photographic emulsion. Tintypes enjoyed their wi ...

portrait purportedly of Crazy Horse was published by J. W. Vaughn in his book ''With Crook at the Rosebud''. The photograph had belonged to the family of the scout Baptiste "Little Bat" Garnier. Two decades later, the portrait was published with further details about how the photograph was produced at Fort Robinson, though the editor of the book "remained unconvinced of the authenticity of the photograph."

In the late 1990s the original tintype was on exhibit at the Custer Battlefield Museum in Garryowen, Montana

Garryowen is a private town in Big Horn County, Montana, United States. It is located at the southernmost edge of the land where Sitting Bull's camp was sited just prior to the Battle of the Little Bighorn, and the opening gunshots of the battle ...

. The museum says that it is the only authentic portrait of Crazy Horse. Historians continue to dispute the identification.

Experts argue that the tintype was taken a decade or two after 1877. The evidence includes the individual's attire, the length of the hair pipe

A Hair pipe is a term for an elongated bead, more than 1.5 inches long, which are popular with American Indians, particularly from the Great Plains and Northwest Plateau.

History

In 1878, Joseph H. Sherburne became a trader to the Ponca peopl ...

breastplate, and the ascot tie, which closely resembles the attire of Buffalo Bill's Wild West

William Frederick Cody (February 26, 1846January 10, 1917), known as "Buffalo Bill", was an American soldier, bison hunter, and showman. He was born in Le Claire, Iowa Territory (now the U.S. state of Iowa), but he lived for several years in ...

Indian performers active from 1883 to the early 1900s. Other experts point out that the gradient lighting in the photo indicates a skylight studio portrait, common in larger cities. In addition, no other photograph with the same painted backdrop has been found. Several photographers passed through Fort Robinson and the Red Cloud Agency in 1877—including James H. Hamilton, Charles Howard, David Rodocker

David Rodocker (October 13, 1840 – July 29, 1919) was an American photographer active in Champaign, Illinois in the 1860s, Winfield, Kansas, 1871–1919, and traveling through Black Hills, 1877.

Early years

Born in Ashland County, Ohio, in 1840, ...

and possibly Daniel S. Mitchell—but none used the backdrop that appears in the tintype. After the death of Crazy Horse, Private Charles Howard produced at least two images of the famed war leader's alleged scaffold grave, located near Camp Sheridan, Nebraska.

Legacy

In the view of authorChris Hedges

Christopher Lynn Hedges (born September 18, 1956) is an American journalist, Presbyterian minister, author, and commentator.

In his early career, Hedges worked as a freelance war correspondent in Central America for ''The Christian Science Mon ...

, "there are few resistance figures in American history as noble as Crazy Horse," while adding that "his ferocity of spirit remains a guiding light for all who seek lives of defiance."

Memorials

Crazy Horse is commemorated by the incompleteCrazy Horse Memorial

The Crazy Horse Memorial is a mountain monument under construction on privately held land in the Black Hills, in Custer County, South Dakota, United States. It will depict the Oglala Lakota warrior Crazy Horse, riding a horse and pointing to hi ...

in the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black Elk P ...

of South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

, near the town of Berne. Like the nearby Mount Rushmore National Memorial

Mount Rushmore National Memorial is a national memorial centered on a colossal sculpture carved into the granite face of Mount Rushmore (Lakota: ''Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe'', or Six Grandfathers) in the Black Hills near Keystone, South Dakota, ...

, it is a monument carved out of a mountainside. The sculpture was begun by Polish-American sculptor Korczak Ziółkowski, who had worked under Gutzon Borglum

John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum (March 25, 1867 – March 6, 1941) was an American sculptor best known for his work on Mount Rushmore. He is also associated with various other public works of art across the U.S., including Stone Mountain in Georg ...

on Mount Rushmore, in 1948. Plans call for the completed monument to be wide and high.

Ziółkowski was inspired to create the Crazy Horse Memorial after receiving a letter from native Lakota chief Henry Standing Bear

Henry Standing Bear (c. 1874 – 1953) ("Matȟó Nážiŋ") was an Oglala Lakota Chief. A founding member of the Society of American Indians (1911–1923), he recruited and commissioned Polish-American sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski to build the ...

, who asked if Ziółkowski would be interested in creating a monument for the native North Americans to show that the Indian nations also have their heroes. The Native Americans consider Thunderhead Mountain, where the monument is being carved, to be sacred ground. Thunderhead Mountain is situated between Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

and Hill City. Upon completion, the head of Crazy Horse will be the world’s largest sculpture of the human head, measuring approximately tall, more than 27 feet taller than the 60-foot faces of the U.S. Presidents depicted on Mount Rushmore, and the Crazy Horse Memorial as a whole will be the largest sculpture in the world.

The memorial is funded entirely by private donations, with no assistance from the U.S. federal government.Nell Jessup Newton, "Memory And Misrepresentation: Representing Crazy Horse," ''Connecticut Law Review'' (1995): 1003. There is no target completion date at this time; however, in 1998, the face of Crazy Horse was completed and dedicated. The Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation regularly takes the lead in cultural, social and educational events, including the Volksmarch, the occasion on which the public is allowed into the actual monument grounds. The foundation generates most of its funds from visitor fees, with visitors numbering more than one million annually.

The monument has been the subject of controversy. In Ziółkowski's vision, the sculpted likeness of Crazy Horse is dedicated to the spirit of Crazy Horse and all Native Americans. It is well-known that Crazy Horse did not want to be photographed during his lifetime and is reportedly buried in an undisclosed location. While Lakota chief Henry Standing Bear believed in the sincerity of the motives, many Native Americans still oppose the intended meaning of the memorial. Opponents of the monument have likened it to pollution and desecration of the landscape and environment of the Black Hills, and of the ideals of Crazy Horse himself.

Aside from the monumental sculpture, Crazy Horse has also been honored by having two highways named after him, both called the Crazy Horse Memorial Highway. In South Dakota, the designation has been applied to a portion of US 16

U.S. Route 16 (US 16) is an east–west United States Highway between Rapid City, South Dakota and Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. The highway's eastern terminus is at a junction with Interstate 90/U.S. Route 14 (I-90/US 14), concu ...

/US 385

U.S. Route 385 (US 385) is a spur of U.S. Route 85 that runs for 1,206 miles (1,941 km) from Deadwood, South Dakota to Big Bend National Park in Texas.

Route description

, -

, TX

, 545

, 877

, -

, OK

, 36

, 58

, -

, CO

, 317

, 510

...

between Custer and Hill City, which passes by the Crazy Horse Memorial. In November 2010, Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

Governor Dave Heineman

David Eugene Heineman (born May 12, 1948) is an American politician who served as the 39th governor of Nebraska from 2005 to 2015. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the 39th treasurer of Nebraska from 1995 to 2001 and 37th lieu ...

approved designating US 20

U.S. Route 20 or U.S. Highway 20 (US 20) is an east–west United States Numbered Highway that stretches from the Pacific Northwest east to New England. The "0" in its route number indicates that US 20 is a major coast-to-coast route. S ...

from Hay Springs to Fort Robinson

Fort Robinson is a former U.S. Army fort and now a major feature of Fort Robinson State Park, a public recreation and historic preservation area located west of Crawford on U.S. Route 20 in the Pine Ridge region of northwest Nebraska.

The for ...

in honor of Crazy Horse, capping a year-long effort by citizens of Chadron. The designation may extend east another 100 miles through Cherry County to Valentine.

Crazy Horse School in Wanblee, South Dakota

Wanblee (Lakota: ''Waŋblí Hoȟpi''; "Golden Eagle Nest") is a census-designated place on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, located in Jackson County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 674 at the 2020 census, virtually all of who ...

is named after him.

In popular culture

* In the film ''Chief Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse ( lkt, Tȟašúŋke Witkó, italic=no, , ; 1840 – September 5, 1877) was a Lakota war leader of the Oglala band in the 19th century. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by w ...

'' (1955), directed by George Sherman

George Sherman (July 14, 1908 – March 15, 1991) was an American film director and producer of low-budget Western films. One obituary said his "credits rival in number those of anyone in the entertainment industry."

Biography

George Sherma ...

, Crazy Horse is played by Victor Mature

Victor John Mature (January 29, 1913 – August 4, 1999) was an American stage, film, and television actor who was a leading man in Hollywood during the 1940s and 1950s. His best known film roles include ''One Million B.C.'' (1940), '' My Darlin ...

.

* In the film ''Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse ( lkt, Tȟašúŋke Witkó, italic=no, , ; 1840 – September 5, 1877) was a Lakota war leader of the Oglala band in the 19th century. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by wh ...

'' (1995), Crazy Horse is played by Native American actor Michael Greyeyes

Michael Greyeyes (born June 4, 1967) (Muskeg Lake Cree Nation) is an Indigenous Canadian actor, dancer, choreographer, director, and educator.

In 1996, Greyeyes portrayed Crazy Horse in the television film ''Crazy Horse''. In 2018, Greyeyes port ...

.

* The middle-grade novel ''In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse'' (2015) by Joseph Marshall, III tells the story of a young Lakota boy who learns about Crazy Horse from his grandfather.

* An ''Excelsior''-class Starfleet

Starfleet is a fictional organization in the ''Star Trek'' media franchise. Within this fictional universe, Starfleet is a uniformed space force maintained by the United Federation of Planets ("the Federation") as the principal means for conduc ...

starship named after Crazy Horse appears in two episodes of '' Star Trek: The Next Generation.''''Crazy Horse,'' USS Startrek.com http://www.startrek.com/database_article/crazy-horse-u-s-s

*Crazy Horse's life was the subject of a four-part series of the podcast ''History on Fire'' by historian Daniele Bolelli

Daniele Bolelli (born January 11, 1974) is an Italian writer, university professor, martial artist, and podcaster based in Southern California. He is the author of several books on philosophy, and martial arts, including ''On the Warrior's Pat ...

.

References

Further reading

* Ambrose, Stephen E. ''Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors''. 1975. * Bray, Kingsley M. ''Crazy Horse: A Lakota Life''. 2006. * Clark, Robert. ''The Killing of Chief Crazy Horse: Three Eyewitness Views by the Indian, Chief He Dog the Indian White, William Garnett the White Doctor, Valentine McGillycuddy''. 1988. * Marshall, Joseph M. III. ''The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota History''. 2004. * Guttmacher, Peter and David W. Baird. Ed. ''Crazy Horse: Sioux War Chief''. New York Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 1994. 0–120. * McMurtry, Larry. ''Crazy Horse (Penguin Lives)''. Puffin Books. 1999. * Pinn, Lionel Kitpu'se. ''Greengrass Pipe Dancers''. 2000. * Powers, Thomas. ''The Killing of Crazy Horse''. Random House, Inc. 2010. . * Sandoz, Mari. ''Crazy Horse, the Strange Man of the Oglalas, a biography''. 1942. * "Debating Crazy Horse: Is this the Famous Oglala?" ''Whispering Wind magazine'', Vol 34 #3, 2004. A discussion on the improbability of the Garryowen photo being that of Crazy Horse (the same photo shown here). The clothing, the studio setting all date the photo 1890–1910. * ''The Authorized Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part One: Creation, Spirituality, and the Family Tree''. DVD. William Matson and Mark Frethem, producers. Documentary based on over 100 hours of footage shot of family oral history detailed interviews and all Crazy Horse sites. Family had final approval on end product. Reelcontact.com, 2006. * ''The Authorized Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part Two: Defending the Homeland Prior to the 1868 Treaty''. DVD William Matson and Mark Frethem, Producers. Reel Contact Productions, 2007. * Russell Freedman, ''The Life and Death of Crazy Horse''. Holiday House. 1996.External links

The Final Days and Death of Crazy Horse

Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part 1 DVD

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Crazy Horse 1840s births 1877 deaths 1877 murders in the United States Lakota leaders Murdered Native American people Native American history of South Dakota Native American people of the Indian Wars People of the Great Sioux War of 1876 Red Cloud's War People of the American Old West Deaths by stabbing in the United States People murdered in Nebraska Battle of the Little Bighorn